The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali is a body of text that offers a glimpse into the depth of yoga—far beyond the commonly associated set of physical exercises (asanas), meditation, and breathing techniques (pranayama).

Yoga, in its essence, is a holistic approach to well-being. Its teachings are rooted in a rich history and philosophy that have evolved over thousands of years with one goal: guiding people to a better life by balancing the mind, body, and spirit. This is how yoga provides a pathway to self-discovery and inner peace with a focus on mental discipline, ethical standards, and meditation.

So, if you like yoga and want to learn more about its philosophy and history, understanding the sutras is a good place to start.

The Story of Patanjali

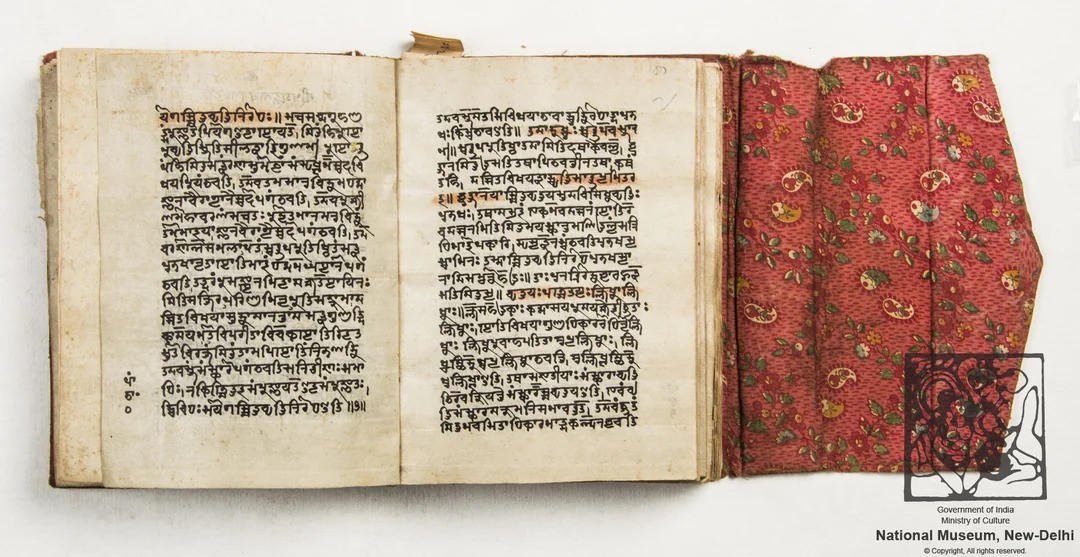

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are an ancient Indian text—a collection of Sanskrit sutras or aphorisms considered to be the foundation of yoga’s philosophy and practice. As the name suggests, the sutras were composed by the sage Patanjali, likely between the 2nd century BCE and the 4th century CE. However, the exact time is not known.

Because it was such a long time ago and not many historical records remain, the story of Patanjali is shrouded in mystery. He is celebrated as a sage, meaning a profound philosopher with sound judgment, who is believed to have contributed to a large body of texts in ancient Indian philosophy. Some of the works attributed to Pantajli, such as the Mahābhāṣya, are still debated and some even believe that the sage Patanjali is actually a name that several different authors used at the time.

Whatever the case, Patanjali's legacy, particularly through the Yoga Sutras, has had a lasting impact on various aspects of Indian philosophy, spirituality, and practice. The text was one of the first successful attempts at systematizing and consolidating earlier traditions of yoga in a practical and easier-to-understand guide that anyone can follow.

And here’s what we have learned from it.

The Yoga Sutras

Patanjali’s yoga sutras comprise 196 aphorisms divided into four chapters (padas). Each pada focuses on a different aspect of the yoga journey. With both theory and practice, the sutras guide the reader toward achieving the ultimate goal: liberation and enlightenment.

Chapter 1: Samadhi Pada (Concentration)

The Yoga Sutras start with the samadhi pada, or concentration—where Patanjali lays the foundation for the philosophical and practical aspects of yoga.

The chapter consists of 51 sutras (aphorisms) that explore the nature, means, and states of concentration, leading to the attainment of samadhi, which is the highest state of meditative consciousness or spiritual union.

Here, Patanjali defines yoga; discusses the different types of concentration that lead to samadhi; outlines the obstacles that you may encounter along the way; explains the role of the practice in overcoming those obstacles; and describes the different states of samadhi.

Chapter 2: Sadhana Pada (Practice)

In the second chapter, titled sadhana pada (practice), Patanjali focuses on the practical aspects of yoga. He outlines the means or methods (sadhana) to achieve the state of samadhi as defined in the first chapter.

This chapter is particularly important for yogis because here Patanjali presented the eightfold path to yoga, i.e. the so-called Eight Limbs of Yoga, which many practitioners have at least heard mentioned in passing.

Sadhana Pada consists of 55 sutras that cover a broad range of topics, including:

- Kriya yoga – a practice consisting of three components: tapas (discipline leading to body and sense control), svadhyaya (self-study or study of sacred texts), and ishvara pranidhana (devotion and surrender to a higher reality).

- The Five Kleshas (Afflictions) – ignorance (avidya), egoism (asmita), attachment (raga), aversion (dvesha), and fear of death (abhinivesha).

- Ashtanga yoga (The Eight Limbs of Yoga) – the central concept in sadhana pada, where Patanjali outlines the eight limbs of yoga as a comprehensive system for spiritual growth.

Essentially, the second chapter is the actual practical guide that teaches readers how to transform their lifestyle and mental outlook.

Chapter 3: Vibhuti Pada (Powers)

The vibhuti pada delves into more advanced practices and the extraordinary abilities that emerge as a result. In the 56 sutras, this chapter moves away from the foundations established in the previous chapters and describes the development of higher states of consciousness and the manifestation of super-human powers or siddhis that practitioners can achieve by dedicating themselves to the eight-limbed path of yoga.

Here, Patanjali gives a more detailed explanation of the final three limbs of yoga: dharana, dhyana, and samadhi; explains how to acquire the siddhis, which are not the goal of yoga, but rather milestones on the path to liberation; and explores the concept of liberation in more depth.

Chapter 4: Kaivalya Pada (Liberation)

Patanjali dedicates the fourth and final chapter of the Yoga Sutras to the ultimate goal of yoga: kaivalya, or absolute freedom and liberation. The chapter, consisting of 34 sutras, gives a more philosophical outlook on kaivalya and the process of achieving liberation from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

In other words, kaivalya pada ties together the practical and metaphysical aspects of yoga, dives deep into the nature of consciousness, the mechanics of our actions and their consequences, and the realization of the self as distinct from the physical and mental experiences.

In this chapter, you can learn about:

- the nature of liberation as a state of ultimate freedom and independence

- viveka-khyati, a process of discerning knowledge

- purification and control of the mind (as a tool for achieving liberation)

- karma, the causal chain of actions and consequences

- the path to liberation

Patanjali's discussion in this final chapter serves as a guide for practitioners who wish to overcome the physical and mental constraints in their lives and achieve the highest state of spiritual liberation.

The 8 Limbs of Yoga

Let’s go back a bit to the sadhana pada. In the second chapter about practice, Patanjali introduces several key concepts, including the eight limbs of yoga or the eightfold path to yoga.

The concept of the eight limbs of yoga has gained significant popularity and recognition in contemporary yoga. Whether you’re a dedicated practitioner or a new enthusiast, chances are that you have heard of this concept already.

There are many reasons for this, but it’s probably because the system represents the first and most practical framework for practicing yoga. If you want to know what yoga is and how to practice it, the eightfold path is a clear guideline accessible and applicable to practitioners of all levels.

In addition, because the eightfold path covers aspects from moral conduct to physical health and mental discipline, it appeals to a broad audience seeking holistic well-being. Yet, it’s still aligned with modern practices—the physical postures (asanas) and pranayama (breathing) are a big part of it. In fact, many modern yoga styles and schools explicitly base their teachings and practices on the eight limbs.

Let’s explore them further.

What Are The Eight Limbs?

Each one of the eight limbs represents an essential element of a holistic yoga practice. Together, the limbs are meant to lead practitioners to a meaningful and purposeful life.

1. Yama (restraints or moral disciplines)

The yamas are universal moral commandments or ethical guidelines regarding our behavior towards others. They consist of five principles:

- Ahimsa (non-violence): having compassion and not harming any living beings.

- Satya (truthfulness): being truthful in one’s thoughts, words, and actions.

- Asteya (non-stealing): no stealing in any form, including material items, ideas, or time.

- Brahmacharya (self-restraint or moderation): not wasting one’s energy.

- Aparigraha (non-greed and letting go of things): letting go of greed and materialism.

2. Niyama (positive duties or observances)

The niyamas are personal practices related to one’s internal world. They focus on self-discipline and spiritual duties. Just like the yamas, the niyamas are based on five principles:

- Saucha (purity): keeping the mind and body clean and healthy.

- Santosha (contentment): being content with what one has.

- Tapas (austerity or self-discipline): having discipline in the pursuit of spiritual and personal growth.

- Svadhyaya (self-study): doing introspection and studying sacred texts to understand oneself and the divine.

- Ishvara Pranidhana (surrender to a higher power): surrendering of the ego and dedicating oneself to a higher purpose.

1. Asana (physical postures)

This is one we probably all know. Asana refers to the physical postures in yoga, such as downward dog, cobra pose, and so on. According to Patanjali, a holistic yoga practice involves taking care of one’s body through the practice of asanas. They’re designed to improve strength, flexibility, balance, and to prepare the body for meditation. The asanas are not meant to push boundaries. Instead, they should reduce discomfort and improve concentration.

2. Pranayama (breath control)

Pranayama involves techniques for controlling the breath. Since breathing is highly associated with the body’s emotional state, regulating it is believed to calm the mind and release negative energy.

3. Pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses)

Pratyahara is the process of drawing one’s attention and focus from the external surroundings to the internal sensations. It’s a crucial step in preparing the mind for meditation, as it helps in reducing the noise in our heads and minimizes our sensitivity to the distractions in our surroundings.

4. Dharana (concentration)

After you master pratyahara, dharana will follow. The concept refers to one’s ability to focus on something without the mind wandering. And, withdrawing the senses is the first step in achieving focused concentration. Dharana practices include trataka (candle gazing), visualization, and focusing on the breath.

5. Dhyana (meditation)

You can think of dhyana as a more advanced dharana. It’s a meditative state that results from sustained concentration. This is a state when we’re completely absorbed in the focus of our meditation, and not just intently concentrating on something. It usually leads to a sense of oneness with the world around you and inner peace.

6. Samadhi (bliss or enlightenment)

The word samadhi, which means bliss or enlightenment, is the last step of the eightfold path to yoga. At this final stage, practitioners will experience a state of oneness with the world around them—a realization of life as is, where the individual consciousness dissolves into a universal consciousness. In Patanjali’s view, this state is the ultimate goal of yoga.

The Legacy That Keeps On Giving

Composed millennia ago, the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali continue to inspire new yoga generations and be a source of wisdom for practitioners on a quest for spiritual liberation and personal growth. Truly, Patanjali’s systematic approach to yoga has transcended the boundaries of time and culture, offering a timeless guide to a balanced, peaceful life and a connection with something larger than our individual selves.

The Yoga Sutras have not only laid the groundwork for contemporary physical practices but also outlined important mental disciplines and ethical considerations that make yoga stand out as a unique approach to life, health, and well-being.

Because of this, the legacy of the Yoga Sutras, with its insights into human nature and the path to liberation, remains an invaluable treasure for all aspiring yogis.

Comments

Existing Comments